Stress. We all experience it. Some stress is good while other stress is bad. Some of it is very bad. No brainer, right? But how does our body process it?

Stress is a part of every day life. It’s important for our body to learn how to process stress. In other words, we need to learn how to regulate.

Learning how to regulate our stress or regulate our emotions can be easier when we understand how our body processes stress.

Learning how our body works can also help us be supportive of our children when they experience stress.

So what is the purpose of our stress response system?

Simply, it’s our natural ability to respond to threats in all forms in order to protect ourselves. And our body is designed to help us do just that.

Do you want the nitty gritty? Or the summary?

This article is jam-packed full of details which could be overwhelming for some. If you aren’t interested in understanding the stress response system at this level of detail, feel free to skip ahead to the summary!

How does the body respond to stress?

Our natural stress response system is sometimes referred to as the fight or flight response system, and it’s a complex system our body uses that allows us to perceive and respond to stimuli in our environment.

The stress response system responds one way if the stimuli is perceived to be safe. It responds another way if the stimuli is perceived to be a threat. This system is designed to help us maintain homeostasis, or balance, in the body.

Although this response occurs rather automatically, there are things that influence it. For example, supportive relationships with adults help children to develop a healthy stress response system. In other words, supportive relationships help the stress response system regulate in a healthy way for children.

On the other hand, childhood adversity and extreme, long-lasting stress can impede healthy development. This can cause damage that leads to lifelong problems with health, learning, and behavior.

Before I get into how the stress response system works, I’ll start by defining stress.

Defining stress and anxiety

Stress and anxiety are related but are different responses in the body. The differences can be important.

Stress

Stress is a physical/biological change or response in the body to an outside stimulus. The factors or experiences (stimuli) that cause stress are called stressors.

There are two types of stressors. First is psychosocial stressors. These are real or imagined environmental events that trigger a stress response. Second is biogenic stressors. These stressors directly cause a stress response, such as caffeine, nicotine, and amphetamines. Most stressors are psychosocial stressors.

A variety of factors or experiences can cause stress. For example: major life events, meeting new people, physical pain, and trauma. All of these are examples of psychosocial stressors. Different stressors cause different stress responses, which I cover further down in this article.

Anxiety

Anxiety is different from stress. It is a state of uneasiness or apprehension or being overwhelmed. It’s the feeling of fear and apprehension in response to a real or perceived threat.

Natural stress response system

As I have said, the stress response system is a complex biological system in our bodies. It integrates several brain structures and includes all of our organ systems. I’ll summarize the system here.

The stress response system begins with receiving stimuli. When we experience stimuli, we evaluate it. In other words, we process the information and determine whether the stimuli is a stressor.

Two main factors determine our response to a stressor. First is how we perceive the stressor. Second is our general state of physical health, including both genetics and behavioral or lifestyle choices. These factors relate directly to how we respond to the stressor.

I’m sure you can confirm that you respond to stress differently when you’re sick than when you’re well. Or if you’re exhausted.

This is an example of why something that I perceive to be a stressor may not be one for you. This is an individual process and often occurs subconsciously.

Our stress response system is activated when we determine there is a threat. Our response occurs in stages. Let’s go over those.

Stress response stages

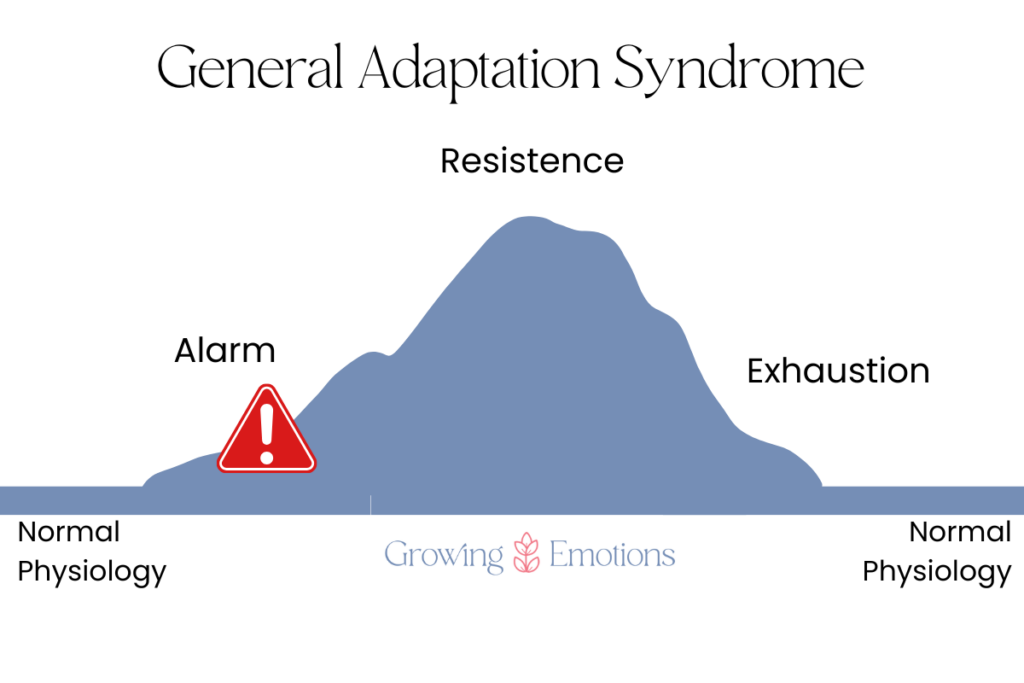

We respond to stress in three stages: the alarm stage, the resistance stage, and the exhaustion stage. The term used to describe this process is General Adaptation Syndrome.

The first phase includes a release of hormones into the bloodstream. These hormones go to specific areas of the body and cause a variety of changes. These changes may be physiological, psychological, or emotional and are intended to increase our ability to address the threat. They are short-lasting and happen very quickly.

The second stage also includes a hormonal response. The previous changes disappear and we are now given resources that provide longer-lasting responses. This is also the stage where the body works to reestablish and maintain homeostasis (balance).

Once the threat has passed, our response to it ends. Our body enters a recovery period where stress hormones are removed and we rebuild energy so we can respond to our next threat.

If our body is unable to recover, specific organs (or our whole body), may become exhausted. In other words, there may be symptoms of dysfunction or disease.

How does our natural stress response system work?

Let’s go over what this looks like in the body. In order to understand our natural stress response system, it’s helpful to first understand the basics about our nervous system. Our nervous system is responsible for the transmission of communication across our entire body. Our nerve cells not only provide sensory input, they also tell our body how to react through the messages they send.

Nervous system

Our nervous system has two parts: the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system includes the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system connects the central nervous system to the rest of our body.

The peripheral nervous system is divided into two networks: the somatic nervous system and autonomic nervous system. The somatic nervous system is under our control. For example, we use it to see a cup on the table and then we use it to move our arm and hand to pick up the cup.

The autonomic nervous system is not in our control. It includes involuntary or unconscious control. It’s responsible for regulating the body’s internal system. For example, if we smell a flower and it tickles our nose, we sneeze. The sneeze is automatic, we don’t control it! That’s the autonomic nervous system in action.

The autonomic nervous system is made up of three parts. The first is the enteric nervous system. It’s responsible for the gastrointestinal tract. We won’t focus on that part. The other two parts, the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system, are directly involved in our stress response.

When the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems function normally, they work in opposition of each other and help us maintain balance. The sympathetic nervous system activates to make our body respond to stress; the parasympathetic nervous system activates to calm and restore our body once the stress has passed.

The two phases of the natural stress response system

The body’s natural stress response system occurs in two phases. The first phase relies on the sympathetic nervous system and the second phase relies on the parasympathetic nervous system. As shown above, the first phase helps us take action and the second helps us restore.

Phase 1: Sympathetic-adrenomedullary system

Phase one begins with awareness of a threat. Our first response to danger is really fast thanks to the sympathetic nervous system.

When we sense a threat, the amygdala (the emotion/fear center of the brain) sends a message to the hypothalamus (the control center of the brain). The hypothalamus then activates the sympathetic nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system tells the adrenal glands (glands that produce hormones) to release adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) into the blood stream.

Once these hormones are released, we receive a burst of stimulation that affects specific areas of the body. This process takes only a couple of seconds and the hormonal response in the body lasts only a few minutes. It’s designed to allow us to either immediately fight or immediately flee whatever danger we face.

Here are some ways our body responds to the release of adrenaline and noradrenaline:

- Increased blood pressure and heart rate

- Increased blood supply to brain

- Increased oxygen in the lungs

- Decreased blood flow to kidneys and gastrointestinal system (prevents urination and defecation while responding to threat)

- Increased sensory perception

If the threat is brief and temporary, the body enters the exhaustion stage. Conversely, if danger persists or is determined more threatening than initially believed, our body enters phase two.

Phase 2: Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (HPA axis)

Phase two also begins with the amygdala sending the hypothalamus a signal. This message is different though. It alerts the hypothalamus that a bigger stress response is needed.

When this happens, the hypothalamus releases a hormone called corticotropin-releasing hormone. This hormone stimulates the pituitary gland, a gland that regulates hormones in the body.

The pituitary gland releases another hormone called adrenocorticotripic hormone. This hormone stimulates the adrenal glands. The adrenal glands release cortisol, sometimes referred to as the stress hormone, into the blood stream.

Cortisol lasts longer and has stronger effects than adrenaline and noradrenaline. In fact, cortisol levels peak between 20 and 40 minutes after the stressor presents itself. Here are some ways our body responds to the release of cortisol:

- Increased production of glucose and reduced insulin sensitivity

- Increased blood clotting and blood pressure

- Appetite suppression, slowed digestion, and increased metabolism

- Suppressed immune system

- Psychological effects such as depression and helplessness

These are but a few of the body’s responses to cortisol, all of which are designed to allow us to respond immediately to a threat.

Cortisol then attaches to special areas on the brain, such as the hippocampus, which leads to the release of gamma-aminobutyric acid, an inhibitory neurotransmitter. This neurotransmitter stops the release of norepinephrine and the corticotropin-releasing hormone. It does this in order to bring the body back to homeostasis. Returning to baseline happens about 40 to 60 minutes after the stressor ends.

Types of stress response

We all experience stress as a part of normal life. And not all stress is bad. Learning how to cope with and respond to stress is important for development. Doing so allows the development of a healthy natural stress response system. Our body’s functioning may be damaged if stress is extreme, long-lasting, or we struggle to manage it.

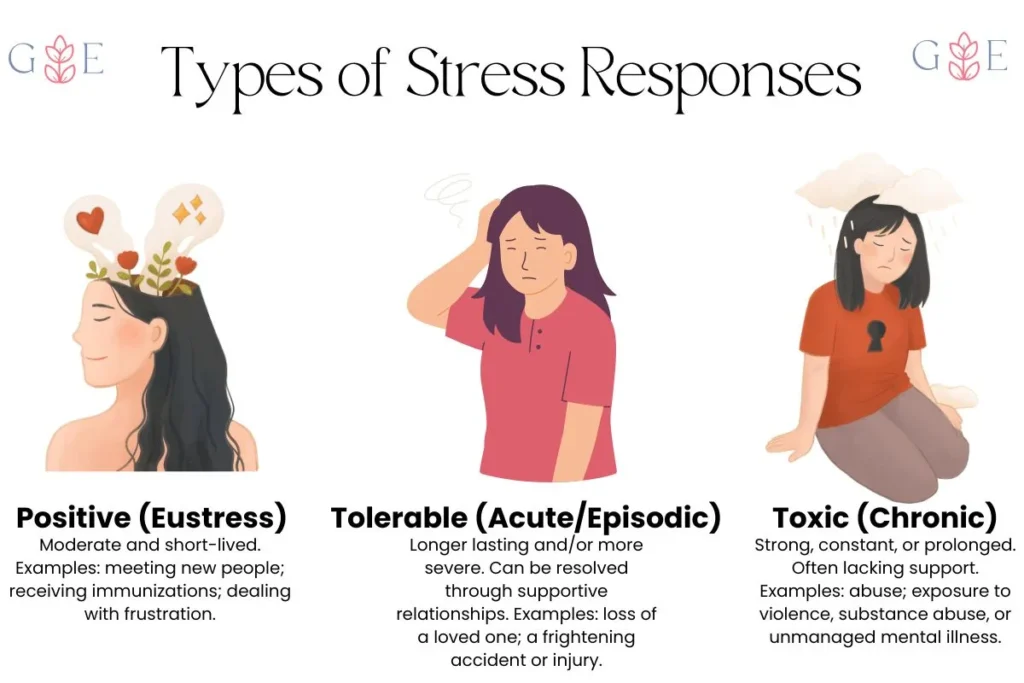

There are three main types of stress responses.

Positive stress response (eustress stress)

As I mentioned, not all types of stress are bad. Stress responses that are moderate and short-lived are positive stress responses. This includes brief increases in heart rate and small changes to our hormone levels.

Stressors that cause a positive stress response are those a child can learn to control and manage well when they have a supportive caregiver. Examples include meeting new people, receiving an immunization, dealing with frustration, or overcoming a fear.

As you can see, some of these stressors can improve our health and well-being.

Tolerable stress response (acute/episodic stress)

The second type of stress response involves a type of stress or threat that is longer-lasting and/or more severe. Examples include the loss of a loved one due to death or divorce, a frightening accident or injury, or lasting discrimination.

Similar to positive stress, experiencing tolerable stress with a supportive adult can buffer the effects of stress for children. In other words, supportive relationships can protect someone experiencing tolerable stress from potential damaging effects.

Toxic stress response (chronic stress)

The third type of stress response is referred to as toxic stress. It refers to stress that causes strong, constant, or continual activation of the natural stress response system.

Examples of toxic stress include physical or emotional abuse, exposure to violence, a caregiver’s substance abuse or unmanaged mental illness, or prolonged financial distress. The absence of a supportive relationship increases the risk of negative effects.

Effects of toxic stress

Toxic stress can disrupt brain development and other organ systems, increase the risk of disease, and have long-term effects on the nervous system. When it occurs constantly or when someone experiences multiple forms of toxic stress at once, there can be a cumulative effect on the person’s physical and mental health.

The more toxic stressors one experiences in childhood, the more likely they are to experience health-related problems throughout their life. In fact, when toxic stress is experienced early in life, the effects are longer-lasting than when it occurs as adults.

Toxic stress can also change the body’s stress response system so much that it activates in response to events that may be minor or not stressful to others. This in turn causes the stress response system to turn on more often and stay activated longer than it would otherwise. This of course increases the risk of negative long-term effects even more.

Individual difference

It’s important to note that not all people are affected by stress, toxic or otherwise, in the same way. This difference could be due to genetics. It could also be due to other factors, such as resilience and coping skills.

Resilience and coping

It is critical to develop coping strategies and/or resilience to help manage stress. It’s important to use coping strategies that promote long-term, rather than short-term, health whenever possible.

There are key factors that can help one cope or build resilience. I’ve provided several examples below.

- At least one stable, supportive relationship. This could be a parent or caregiver, friend, teacher, coach, or other adult. This is particularly true if the child has a secure attachment figure.

- Understanding emotions and developing emotion regulation and emotional literacy.

- Building self-esteem, self-efficacy and self-control.

- Developing skills that promote wellness, such as physical exercise, healthy eating, and healthy social-emotional development.

- Facing fears and using problem-solving techniques.

Summary

Woah boy that was a lot of information! Let’s sum it up, shall we?

We experience various types of stress on a regular basis. Some forms of stress are positive. If our stress response system is healthy, it responds to positive stress smoothly and easily.

Some forms of stress are challenging and yet tolerable, specifically if we have positive support to help us through it.

However, there’s also toxic stress. When we experience toxic stress, our stress response system can become damaged. The part of our stress response system that releases cortisol (the stress hormone) into our body can become “stuck in the on mode.”

Unfortunately, this means that our stress response system never regulates.

Building coping mechanisms can help us with all three types of stress responses.

Our natural stress response system is complex and powerful. It provides us with protection from threats and helps us build healthy ways of managing day-to-day stressors. It can also cause illness and maladaptive behavior if we aren’t able to manage it.

Understanding our stress response system and it’s functioning can be instrumental in managing our own stress and supporting our children’s development in healthy ways.

Register for my FREE Intro to Anger Management Course

Are you struggling to manage your anger? If so, then this free Anger Management Course is for you.

References and recommended resources

- Everly Jr., George. S. & Lating, Jeffrey M. (2013). A Clinical Guide to the Treatment of the Human Stress Response. 3rd Edition. Springer New York DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-5538-7

- Folk, J. (2021, May 15). Anxiety 101. Anxiety Centre. https://www.anxietycentre.com/articles/anxiety-101/

- Folk, J. (2021, May 19). Stress response. Anxiety Centre. https://www.anxietycentre.com/anxiety-disorders/symptoms/stress-response/

- Godoy, L. D., Rossignoli, M. T., Delfino-Pereira, P., Garcia-Cairasco, N., & Umeoka, E. H. (2018). A comprehensive overview of stress neurobiology: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 12 (127). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00127

- Harvard University: Center on the Developing Child (n.d.). Toxic Stress. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/

- Kemeny, Margaret E. (2003). The psychobiology of stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(124), 124-129. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01246

- Kindsvatter, Aaron & Geroski, Anne (2014). The impact of early life stress on the neurodevelopment of the stress response system. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00173.x

- Let’s Talk Science. (2020, July 29). Stress and the brain. https://letstalkscience.ca/educational-resources/backgrounders/stress-and-brain

- McEwen, Bruce S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine 338 (3), 171-179. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199801153380307

- Modell, H., Cliff, W., Michael, J., McFarland, J., Wenderoth, M. P., & Wright, A. (2015). A physiologist’s view of homeostasis. Advances in Physiology Education 39, 259-266. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00107.2015

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2005/2014). Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing brain: Working paper 3. Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu

- Yaribeygi, H., Panahi, Y., Sahraei, H., Johnston, T. P., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI Journal 16, 1057-1072. http://dx.doi.org/10.17179/excli2017-480